Delhi, 1948. In the first year after independence from the British Raj, this ancient city is reeling. Hundreds of thousands of families who fled bloody religious strife are on the move — Indian Muslims to Muslim-dominated Pakistan, Hindus and Sikhs to Hindu-dominated India. Countless emigres — many of them arriving here in the capital — are suddenly homeless, without work or ways to support their families.

In Darayaganj, a working-class area that straddles Old and New Delhi, a Hindu family from Pakistan regroups, struggling to make a living cooking the kind of food they left behind.

Soon, households in the better parts of town are sending car and driver to the family’s rowdy street side stalls to fetch juicy chicken and chunks of lamb and light fluffy breads — all of them roasted in a fiery hot, open clay oven called a tandoor. Delhi sophisticates delight in the new “tandoori” dishes they can eat with their hands and take on picnics. An almost instant success, the family stalls grow into a restaurant, Moti Mahal, with music and a tented courtyard and unforgettable food.

“It was a place we all went to,” says Madhur Jaffrey, the New York-based Indian cookbook author and actress, who grew up in Delhi and remembers those years. “It was the most exotic food we’d ever seen — the meats were roasted fast, the insides slightly rare. The breads that accompanied them were huge and light. A new kind of dal {dried split peas, beans or lentils} was baked overnight in earthen containers in the ashes of the oven. It was a whole new way of cooking. Everybody thought it was just grand.”

This week, both India and Pakistan mark the 50th anniversary of their independence from British rule. No one could have predicted that their split-off from the Empire and each other — as well as the entrepreneurial energies of one refugee family — would lead to a taste for tandoori foods that has traveled deep into India and all over the world. THE METHOD BEHIND THE NAME

Tandoori Murgh (marinated whole roast chicken). Seekh Kebab (spiced ground lamb in sausage-like patties on a skewer). Jheenga Kebab (marinated skewered shrimp). Naan (a slightly leavened, fluffy white bread). These exotic-sounding foods may be spiced similarly, but what makes them “tandoori” is their cooking method — over red hot coals in a high-intensity-heat clay oven.

Tandoori chicken, meats and fish are marinated in a spicy yogurt and cooked quickly in this very high heat. The film left on the food by the yogurt helps retain flavors and juices, and the oven itself yields an earthy aroma of the clay. The final product is tender and flavorful.

The resettled family of Moti Mahal introduced tandoor cooking to Delhi, but where did the style come from in the first place? Even now the ovens are too bulky for home use. Besides, much of India is vegetarian. So who thought to cook meat on skewers over a charcoal flame in a clay oven, or bake bread by sticking flattened patties of dough to the upper insides of that oven?

Tandoori foods as we know them emerged from the meat-eating areas of Afghanistan, Pakistan and India known as the Northwest Frontier. Indian cookbook author and food historian Julie Sahni thinks the style originated with the Bedouins, perhaps from the area around Syria or Iraq.

“This kind of cooking is synonymous with a nomadic life-style,” she says, elaborating: “Dig a cooking pit, cook, close it up and move on.” She speculates that at first the ovens were used strictly to bake bread, whereas meats — perhaps threaded on a sword — would be cooked over the fire, or the makeshift lid of the oven. “So if they wanted to cook a large piece of meat, someone would have to stand there and turn it,” she explains.

But as the style made its way through Central Asia, she says, something happened: People began to put the skewered meats inside the oven, where they cooked very quickly because of the intense heat of the coals. Sahni believes the change in the process took place on the Indian subcontinent.

“Some creative guy figured out how to line up the skewers right over the open fire,” she says, speculating that by the 19th century meat cooked this way might even have been sold by street vendors. “It was a great method — they could skewer and roast close to eight chickens at the same time.”

Madhur Jaffrey also believes the style made its way from Central Asia (where breads that rose only slightly had been cooked in clay ovens for hundreds of years) through Uzbekistan, Afghanistan and the Northwest Frontier region to India. “There were constant invasions {through the Northwest} from those passes,” she says.

As for the breads, slightly leavened breads have been cooked in clay ovens in India for centuries and still are. Ashok Bajaj, the owner the Bombay Club in downtown Washington, remembers taking pieces of unbaked dough to the local community oven for his mother when she didn’t feel like making 30 pieces of bread for a meal.

Tandoori chickens and meats seemed to emerge in India in Muslim-dominated areas, for example the part of India that became West Pakistan. North India, with its 16th- and 17th-century history of meat-eating Moghuls, and Delhi, which had had a large Muslim population before 1947, were natural new homes for tandoori foods.

And the meat preparations weren’t spicy. “People from this part of the world weren’t eating spicy food at all,” says Jaffrey. Tandoori “would have had a mild flavoring — probably a little garam masala, ginger, garlic, onion, lemon juice, yogurt. But very light, very mild.”

But despite its exotic appeal, tandoori wasn’t accepted by everyone immediately. (For that matter, India had no tradition of restaurant eating at that time.) Some families feared the lower-class origins of the new food. “High-class people, society people, wanted to eat that food, but they wouldn’t be seen eating it there,” Sahni explains. “It wasn’t elegant — it was a ruffian style of eating” — hence the chauffeur-driven cars sent to take the food home.

But tandoori cooking caught on soon enough — even in some of the new grand restaurants, like Gaylords or the Kwality in New Delhi. “You went to eat the more exotic foods,” says Jaffrey. “Then all the restaurants around began to copy the food. And as imitators began to crop up, tandoori food became a restaurant staple.”

And not only in Delhi. “North Indian cuisine is famous now all over India,” says Rajiv Ahuja, the Bombay-born manager of the Bethesda branch of the Indian restaurant Haandi, which features many tandoori dishes.

These days tandoori food can be found in restaurants from Palo Alto to Paris, Boston to Bristol, Edinburgh to Ann Arbor — and of course particularly in areas where there is a large South Asian community, like Washington. MEANWHILE BACK IN D.C.

At The Bombay Club just off Farragut Square in the District, it’s 9 o’clock in the morning — time to fire up the tandoors to ready them for the lunchtime crowd. Last night’s ashes are still smoldering, but bags of charcoal need to be added.

The restaurant’s master tandoori chef, Mahipal Negi, 38, has been delayed, so Delhi-born executive chef Sudhir Seth, 40, stirs the ashes in the two side-by-side ovens and adds a bag of charcoal to each. He piles the lumps of charcoal on a slant — from almost none on one side of the oven to one-third of the way up the side on the other.

The goal is an intense heat — certainly more than 500 degrees, and some chefs even estimate as high as 800. The side where the charcoal is piled higher is hotter; the middle ground has a medium heat; and the interior wall of the oven near the top is the right temperature for baking the breads — naans, parathas, kulchas — that are cooked in a tandoor.

The ovens, shaped like a skirt that balloons slightly and then drifts to the ground, sit next to each other in a rectangular unit faced with white tile (some restaurants have freestanding units surrounded by stainless steel); the tandoors are separated from each other and the surrounding tile by a brick fire wall. Circular vents behind the ovens — two above the tiled surface and two just below the ovens can be opened to release steam and regulate the fire.

Now Negi, who learned his trade at 12 and has been cooking tandoori foods ever since, arrives, checks the ovens, adds more charcoal, cleans the tile surrounds and organizes his utensils. The fire going, he flicks a drop of oil above each tandoor, folds his hands in a quick prayer and gives thanks. “In our region, fire is one of the gods,” says Negi, who is from Dehradun, 2,000 feet up in the Himalayan foothills.

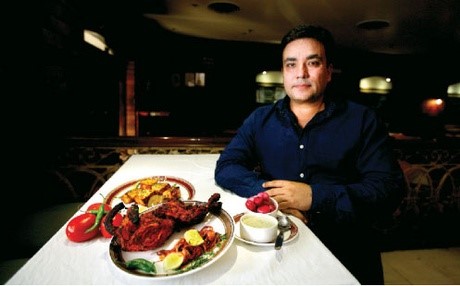

“The best tandoori chefs are from the hills,” Bombay Club owner Bajaj confides.

Throughout the morning, Negi will return to check the fire. The top layer of charcoal will keep burning off, but he can adjust it by adding more charcoal or by closing off the tops with their metal lids.

The fire under control, Negi turns to the marinades for the tandoori fish on the menu. (The chicken and lamb have been marinating overnight). Although many of the ingredients are the same — ginger, garlic, garam masala, cumin, turmeric, salt, white pepper, lemon or lime juice, oil and yogurt — not all the spices are used for each dish, and, of course, the proportions differ.

This day Negi is working with separate tubs of shrimp, scallops, swordfish and rockfish. He sprinkles spices on each, then adds dollops of garlic and ginger paste, then soybean oil and lemon juice, before using his hands to distribute the ingredients evenly on the fish. “It’s only a hint of each spice,” he says, “but there are many spices.”

Then he adds yogurt and mixes again before returning each tub to a walk-in refrigerator. (More yogurt will be added just before cooking. “Most of the yogurt drips off,” says executive chef Seth.)

Negi washes his hands between each step, not only for sanitary reasons, but also to keep the flavors and smells of the marinade in one tub of fish from carrying to another. (Turmeric and red spices, for example, are not used with rockfish.)

The fish taken care of, Negi checks the chickens. Is the marinade seeping into the chicken properly? Are the bones exposed? (They should be, in order to conduct the heat.) He moves the chickens to a clean tub, and adds a second yogurt marinade.

Less than an hour has passed since Negi arrived, but he’s ready to turn to the bread dough. He tears off small chunks, rolls them in flour and sets them to rest on a large tray. Some pieces of dough get stuffed, with onion, cilantro, caraway seeds (“It’s good for digestion,” says Negi); others get twisted. Seth, who has watched Negi work for years, is nevertheless awed by his colleague’s skills. “The stuffing would fall out for almost anyone else,” he says. TANDOOR AS AMBASSADOR In America, Indian food is not as familiar as other ethnic cuisines, according to the most recent study done by the National Restaurant Association. It ranks among the least-known cuisines, along with Thai, Middle Eastern, Vietnamese and Korean, which tend to be known by fewer than one-fourth of all consumers.

However, the Washington area is blessed with eateries of all stripes generated by foreign nationals who have come to live here. And restaurant-goers in search of Indian food have their choice of Kashmiri curries laden with spices and almonds, or the fiery hot vindaloo dishes of South India or Moghlai specialties with creamy sauces redolent with cardamom and cinnamon.

But what do many of us order?

Tandoori.

Why? For one thing, we know what we’ll get. Although the quality of the cooking may vary, the dish doesn’t (or shouldn’t). And it’s less intimidating for the uninitiated to opt for tandoori than to make their way through an entire Indian menu.

Another reason Americans choose tandoori, say Indian restaurant owners, is that they’re made with fish, skinless chicken or cubes of lean meat, and are therefore lower in fat than what we think of as traditional curries. They are marinated, not steeped in a sauce.

Finally, tandoori is often what Indian restaurateurs suggest to people new to Indian food. And several Indian restaurants label their tandoori dishes “Indian barbecue,” a very reassuring term. Says the Bombay Club’s Bajaj, “The barbecue connection works for Americans. It’s a good way to get used to the spices gently.”

Home chefs familiar with Indian foods and Indian spices can of course make tandoori foods on a barbecue grill with a lid, or in the oven. But they’re never quite the same as when they’re cooked in a tandoor. And few people have a clay oven, even in India. So — thanks to the South Asian restaurateurs who have settled in this country — tandoori, like steamed crabs , seems to work best as a restaurant food.

So on this special anniversary of independence from British rule, perhaps a few hip-hip-hoorays for tandoori — the food that arrived with independence — are in order. JULIE SAHNI’S TANDOORI CHICKEN (4 large to 8 moderate servings)

Tandoori chicken is often characterized by its red color, achieved by using edible dye. It is added purely for looks, hence may be left out. Brushing cooked tandoori chicken with melted butter or oil before serving will further add to the appeal and flavor.

8 pieces bone-in, skinless chicken breast halves and legs in any combination

FOR THE MARINADE:

1 1/2 cups plain yogurt

4 tablespoons lemon juice

8 cloves garlic, peeled

2-inch piece fresh ginger root, peeled

2 tablespoons cumin

1 tablespoon coriander

1 teaspoon cayenne pepper

1/2 teaspoon cardamom

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1/4 teaspoon cloves

1/4 teaspoon cinnamon

Kosher salt to taste

1 tablespoon red food coloring (optional)

2 tablespoons yellow food coloring (optional)

TO FINISH:

Olive or vegetable oil (optional)

1 lemon

Trim the fat from the chicken pieces. Using a paring knife, prick the flesh and make diagonal slashes about 1 inch apart. Set aside in a bowl.

Process all the marinade ingredients in an electric blender or a food processor until thoroughly pureed. Pour the marinade over the chicken pieces, toss and rub to coat pieces thoroughly. Cover and refrigerate for 8 hours or overnight.

Light and prepare a covered charcoal grill or preheat the oven to 500 degrees.

Remove the chicken from the marinade (reserve marinade) and, if desired, coat lightly with oil. Place the chicken pieces over a well-oiled rack and cook, covered, with the vents open, turning 3 to 4 times and basting with the marinade for 30 to 40 minutes or until the juices run clear when a knife pierces each piece at the joint.

Alternatively, to cook indoors, place the chicken in a single layer over a rack positioned on a baking sheet with a slight lip and bake in the middle level of the oven for about 25 minutes or until cooked, basting once with marinade juices. Serve immediately, sprinkled with lemon juice and accompanied by roasted vegetables (recipe follows).

Per serving: 518 calories, 61 gm protein, 4 gm carbohydrates, 27 gm fat, 189 mg cholesterol, 7 gm saturated fat, 460 mg sodium THE BOMBAY CLUB’S TANDOORI SALMON (8 servings)

One of the most popular dishes at the Bombay Club, Tandoori Salmon has been served at the restaurant since it opened in 1988.

1 tablespoon ginger paste* or very finely chopped fresh peeled ginger root

1 1/2 tablespoons garlic paste* or very finely chopped garlic

1 tablespoon lemon juice

1 teaspoon garam masala*

1/4 teaspoon salt

Pinch ground white pepper

3/4 cup (6 ounces) plain yogurt

Eight 4-to-6-ounce salmon fillets

About 1 tablespoon vegetable oil

Mix the ginger, garlic and lemon juice with the garam masala, salt and pepper. Then combine the mixture with the yogurt, stirring until smooth. Pour the marinade over the salmon fillets. Cover and refrigerate for 3 hours.

Skewer the fish fillets lengthwise, and cook in a moderately hot tandoor (450 to 500 degrees) for 2 1/2 minutes. Remove from the tandoor and allow the excess moisture to drip for 2 minutes. Baste with oil and finish cooking for 1 minute in the tandoor.

Alternatively, preheat oven to 500 degrees. Prepare salmon as above and place fillets on a rack over aluminum foil-lined pan with slight lip. Roast for 5 to 6 minutes. Turn fillets and roast for 4 to 6 minutes more, watching carefully.

* NOTE: Ginger and garlic pastes, as well as garam masala, a spice mixture, are available at many international markets and fancy-food shops.

Per serving: 240 calories, 33 gm protein, 1 gm carbohydrates, 11 gm fat, 91 mg cholesterol, 2 gm saturated fat, 103 mg sodium JULIE SAHNI’S INDIAN ROASTED VEGETABLES (4 large to 8 moderate servings)

To accompany tandoori chicken, Sahni suggests lightly roasted vegetables in place of a salad. It’s best to begin roasting the vegetables about 15 minutes before the chicken is done. Also, you can add a couple of young zucchini, quartered lengthwise.

2 large Spanish onions, peeled and cut into 1/4-inch slices

1 green bell pepper, cored and sliced into 1/2-inch-thick wedges

1 red bell pepper, cored and sliced into 1/2-inch-thick wedges

1 endive, trimmed and leaves separated

1 tablespoon olive or vegetable oil

Kosher salt and black pepper to taste

4 tablespoons minced fresh coriander (cilantro) for garnish

Combine the vegetables with the oil, salt and pepper in a large bowl, and toss well. To cook on a grill: Spread the vegetables on a fine-mesh grate or in a basket placed over the grill rack, and cook, turning the vegetables until they are lightly charred and cooked, about 5 minutes. Serve the vegetables sprinkled with fresh coriander (cilantro).

Per serving: 117 calories, 3 gm protein, 19 gm carbohydrates, 4 gm fat, 0 mg cholesterol, trace saturated fat, 278 mg sodium THE FIRST TANDOORI

Julie Sahni recalls a dramatic first experience with tandoori. “We were at a weekend family picnic,” she recalls. “I was 7. Nobody really knew what the food would be. Suddenly I could see a whole gathering of men go away from the tables. A few of the children climbed up a tree to see what was going on. Behind a bush, there were live chickens running around. As we watched, the men whacked off the heads, cleaned the birds and {applied} a green paste. Even though butchering wasn’t usually done at your doorstep, that didn’t surprise us as much as seeing that they’d dug a hole and built a fire in a public park. We so excited, so scared — we didn’t know if we should have seen any of this — that afterward we just sat there.

— Judy Weinraub A SAMPLING OF AREA’S TANDOOR-SERVING INDIAN RESTAURANTS

There are many, many Indian restaurants in the Washington area. Here are a few that have caught the attention of local food critics and restaurant enthusiasts.

ADITI, 3299 M St. NW; call 202-625-6825. Lively crowds on the weekend.

AROMA, 1919 I St. NW; call 202-833-4700. A beautiful room with a good number of Indian customers at lunch.

BOMBAY BISTRO, two locations: 3570 Chain Bridge Rd., Fairfax; call 703-359-5810; and Bell’s Corner, 98 W. Montgomery Ave., Rockville; call 301-762-8798. The tandoor is king here — food can be terrific.

BOMBAY CLUB, 815 Connecticut Ave. NW; call 202-659-3727. An elegant downtown spot with a decidedly rich and Raj sensibility.

BOMBAY DINING, 4931 Cordell Ave., Bethesda; call 301-656- 3373. A soothing spot in downtown Bethesda’s restaurant zone.

BOMBAY PALACE, 2020 K St. NW; call 202-331-4200. Part of a glamorous international chain; lots of style.

CONNAUGHT PLACE, 10425 North St., Fairfax City; call 703-352-5959. Low-key elegance in the heart of Fairfax. Even the taped Indian music is hushed.

HAANDI, two locations: 4904 Fairmont Ave., Bethesda; call 301-718-0121; and 1222 W. Broad St. (Falls Plaza Shopping Center), Falls Church; call 703-533-3501. Downtown style, plus good food, in the suburbs.

INDIA KITCHEN, Shady Grove Center, 9031 Gaither Rd., Gaithersburg; call 301-212-9174. A pleasant surprise tucked inside a shopping center.

TANDOOR, 3316 M St. NW; call 202-333-3376. A quiet part of Georgetown’s international M Street lineup.