Perhaps the only good thing that can be said for the bloody struggle that followed the partition of Pakistan and India in 1947 is that it forced the great tandoori cooks, who were Hindus, to flee from places like Peshawar, near the Afghanistan border, where they were throwing away their tikkas and kebabs on British air force officers, to the Indian capital of Delhi, where they set the food- loving world on its ear.

JAMES TRAUB is the author of ”India: The Challenge of Change,” published by Simon & Schuster. The first to set up shop was Kundan Lal, and his cousin, also Kundan Lal. The two of them pledged their family’s jewelry, and opened up a dhaba, or roadside diner, on a crowded street in Old Delhi. Most of the restaurants in Delhi at the time were owned by the British and served what was described as British fare. Indian restaurants were primarily vegetarian. Delhi was ripe, not to say desperate, for this tandoori restaurant, whose name was Moti Mahal. Within a year the Nehru family, including daughter Indira Gandhi, had become regular customers.

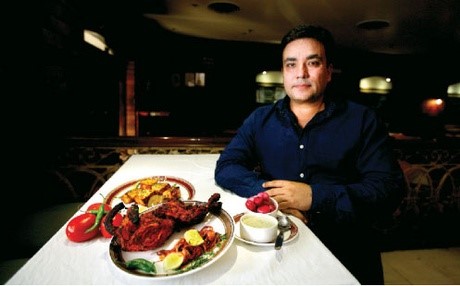

The elder Kundan Lal, who is portly, florid, somewhat dainty in manner and careful in dress, and possessed of splendid moustaches ticks off the names of ministers and heads of state who regularly arrived in his restaurant’s quite unwholesome purlieus. Peace treaties were hammered out in the balcony. And M. Maulana Azad, the great Muslim leader, reportedly told the Shah of Iran that while in India he must make two visits – to the Taj Mahal and Moti Mahal.

The innovation that attracted these grandees – who, incidentally, sat in their cars rather than mix it up with the lumpen on the sidewalk – was the tandoori pit. While the Moghul, or Mughlai, cuisine which had dominated North Indian cooking, is fried on the stove, tandoori meat or bread is baked in a cylindrical clay oven sunk into the earth. The clay surface keeps everything dry and crisp, while the circular air flow, so they claim, insures uniform cooking.

A tandoori kitchen is a primitive affair. At Moti Mahal a pair of lean youths in ancient undershirts sit cross-legged behind a pair of tandoori pits. The pits are fired by wood that is left to burn overnight, and the cooks regulate the heat by stuffing wads of paper into a secondary hole that supplies air. The fellow who makes the meat keeps next to him skeins of chickens, chops and kebobs strung on a skewer. He lowers these into the pit all at once, to prevent overcooking, and inside of 12 minutes or so, they’re done.

It is the bread man, though, who seems to do the really skilled labor. First, he fashions the dough into shape, taking a nip at one end to form the familiar triangular shape of the naan. A really skilled craftsman can fling the dough around like a pizza maker, until he has a vast, thin wedge about two feet from nose to tail and 18 inches across the wings – the so- called ”family naan.” Then he takes his creation and slaps it against the side of the oven. Once it has browned and bubbled out, he dislodges with one long metal prong, catches it with another, and flips it out of the pit. In the kitchen of a really busy tandoori restaurant you can see these rods flying and clicking like a pair of giant knitting needles.

What emerges from these acrobatics is bread that is soft enough to be wrapped around a piece of meat without breaking, but crisp and firm on its underside where it baked against the clay. Naan is also available with potato or chicken or ground beef mixed into the dough, but this seems like a bit of lily gilding. The bread, after all, is your fork and spoon, since cutlery, in tandoori restaurants, is generally discouraged as an unnatural intrusion between diner and dinner.

But it must have been the meat that fetched the Brahmanate of New Delhi into the slums of Old Delhi. Tandoori meat is dry – and yet not dry. Take chicken tikka, for example. A tikka is a boneless chunk of meat marinated for several hours in a paste usually consisting of onion, garlic, ginger, coriander, cumin, turmeric and chili, yogurt and whatever else the chef feels is in order. The chicken may be slowly baked so that it is half done when ordered. Then it will be plunged for a few minutes into the tandoori pit.

It emerges, in the best of all possible restaurants, light pink in the center, crisp on the outside, slightly smoky throughout, and with a fine mist of sauce still clinging to the surface. It is pungent, with cumin and coriander, rather than hot, with chili. One should give in, after the first bite of murg malai, or tender chicken, to the sudden desire to weep; India is an emotional country, after all.

But tandoori is a sturdy frontier cuisine, citified though it may have become. You can always order a hunk of animal instead of little pieces. A few restaurants, including the undisputed tandoori Valhalla, the Maurya Hotel’s Bukhara, serve an entire leg of lamb, known as secunderi raan. This magnificent specimen looks like the drumsticks of a brontosaurus. The meat has been left on the bone, but cut into thick slabs, so that you tear your way down to two gleaming white bones around a joint. On a recent visit, two proper ladies were observed polishing off one between them at an afternoon sitting.

Those who hunger for the basic, unadulterated tandoori can venture even deeper into the heart of Old Delhi, where even the agile three-wheeled rickshaw scarcely ventures. There, in Fatehpuri, behind the great mosque, the Jama Masjid, a few genuine, unevolved tandooris – Moti Mahal, circa 1947 – can be found. At one of these, the Khake da Hotel, a hideous din of slapping comes from the kitchen, as from a crude police interrogation. The prongs clack like mad. Waiters dash back and forth from the tandoori kitchen in the back to the gas ranges in the front – a distance of about 15 feet – clutching scrawny chickens in threadbare towels. I have seen one waiter almost strike another with one of these starved creatures. But no matter. Dress some of that naked poultry in the finery of butter and tomato and mild spices, and a reasonable man will overlook its defects; will, indeed, hum to the background music of smacked bread and crossed needles.

The tandoori trail Choices Delhi abounds in restaurants, especially humble ones, that serve memorable tandoori dishes. The following is a selection. The aptly named Have More Restaurant (12 Pandara Road Market, New Delhi 110003; telephone 387070) makes a great tandoori fish, while the Khyber Restaurant (1/1514 Kashmere Darwaza Gate, Delhi 110006; telephone 220877) is famous for its lamb dishes, especially its secunderi raan, which must be ordered in advance. The tabs at both of these restaurants, as at Moti Mahal (3701 Netaji Subhash Marg, Darya Ganj, New Delhi 110002; telephone 273661 and 273011) will run about $4 a person. Tiny dhabas like the restaurant in the Khake da Hotel (74 Municipal Market, Connaught Circus, New Delhi 110001; telephone 46580) serve meals in the $2 range. And the bill at the Bukhara (Maurya Palace Sheraton Hotel, Sardar Patel Marg, Diplomatic Enclave, New Delhi 110021; telephone 370271, Extension 1972) runs between $5 and $8 a person, without drinks. All of these restaurants are open year round, generally until midnight, but the Moti Mahal is closed Mondays. Normally beer is recommended as an accompaniment to tandoori dishes, but in the better restaurants one can order Indian or imported wine, hard liquor or soft drinks.J. T.